Why am I discussing this paper?

I chose Andronov et al.’s paper[1] because:

- It addresses a critical bottleneck in speeding up predictions of transformer [2] based chemical reaction models

- It creatively applies NLP acceleration techniques (speculative decoding) to chemistry

- The solution requires no model retraining or architectural changes

- The impact on industrial applications could be significant

Context

Computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) is a core technology enabling drug discovery. Modern CASP systems typically combine a machine learning-based single-step retrosynthesis model with a planning algorithm like Monte-Carlo Tree Search. The model proposes possible reactant sets for a target molecule, while the planning algorithm constructs a synthesis tree.

While earlier CASP systems relied on manually encoded rules, researchers now focus on AI-powered methods. Single-step retrosynthesis models come in two paradigms: template-based and template-free models. Template-free models, particularly those based on transformers, offer state-of-the-art accuracy but suffer from slow inference speed, limiting their practical utility in industrial settings.

Prior work

Segler et al. (2018)

Segler et al. [3] outlined the design principles for modern CASP systems: combining a machine learning-based single-step retrosynthesis model with a planning algorithm. This seminal work established the framework that most current CASP systems follow.

Molecular Transformer (2019)

Schwaller et al. [4] introduced the Molecular Transformer, the first encoder-decoder transformer for conditional SMILES generation in reaction modeling. This model served as the foundation for subsequent developments in the field.

The Molecular Transformer formulates both reaction prediction and retrosynthesis as SMILES-to-SMILES translation problems:

Chemformer (2022)

Irwin et al. [6] developed Chemformer, a pre-trained transformer for computational chemistry. While demonstrating impressive accuracy, it retained the slow inference speed characteristic of autoregressive models.

Problem setting

- Template-free transformer models achieve state-of-the-art accuracy in reaction prediction and retrosynthesis

- However, their slow inference speed limits practical utility in industrial applications

- The bottleneck is the autoregressive nature of token generation—each prediction requires a full forward pass

- Previous acceleration approaches (model distillation, architectural modifications) typically compromise accuracy

- There’s a need for acceleration methods that preserve model accuracy without architectural changes

Research Gap: How can we accelerate transformer inference without compromising the model’s predictive power?

Technical Foundations

Transformer Architecture for Chemical Reactions

The Molecular Transformer and its variants use the encoder-decoder architecture: - Encoder: Processes the input SMILES (reactants or products) - Decoder: Generates the output SMILES (products or reactants) token by token

Understanding Decoding Strategies

What is Greedy Search?

Greedy search is the simplest decoding strategy for sequence generation models like transformers. At each step of generation:

- The model calculates the probability of every possible next token

- Greedy search simply selects the single most probable token

- This token is added to the sequence

- The process repeats until an end token is generated or maximum length is reached

Greedy decoding selects the most probable token at each step:

initialize output = [BOS] # Beginning-of-sequence token

while not finished:

next_token = argmax(model_probability(next_token | output))

output.append(next_token)

if next_token == EOS: # End-of-sequence token

breakAdvantages: - Computationally efficient (only one model forward pass per token) - Simple implementation - Minimal computational overhead

Disadvantages: - Often produces suboptimal sequences - Cannot explore alternative generations

Beam Search

Beam search improves upon greedy search by maintaining multiple promising candidate sequences simultaneously:

- At each generation step, expand all current sequences with all possible next tokens

- Score each new candidate sequence based on its overall probability

- Select the top-K highest-scoring sequences to keep (where K is the “beam width”)

- Continue until all sequences have produced an end token or reached maximum length

initialize beams = [[BOS]] # K copies of beginning-of-sequence token

while not all beams finished:

all_candidates = []

for beam in beams:

if beam ended with EOS:

all_candidates.append(beam)

else:

for possible_next_token in vocabulary:

candidate = beam + [possible_next_token]

score = compute_sequence_probability(candidate)

all_candidates.append((candidate, score))

beams = select_top_k_candidates(all_candidates, k=K)Advantages: - Explores multiple promising paths simultaneously - More robust to local decision errors - Produces K different candidate sequences (essential for retrosynthesis) - Generally higher quality outputs than greedy search

Disadvantages: - Computationally more expensive (K times more computation than greedy search) - Slower inference speed - Requires more memory - Still not guaranteed to find the globally optimal sequence

Parameter K (beam width): - Controls the trade-off between exploration breadth and computational cost - Typical values range from 5-20 for chemical reaction models - Higher K values generally produce more diverse candidates but with diminishing returns

Approach

The authors propose applying speculative decoding to accelerate chemical reaction models, with domain-specific optimizations.

Speculative Decoding

Speculative decoding[5] accelerates autoregressive sequence generation by predicting multiple tokens in one forward pass:

- Append a draft sequence to the currently generated sequence

- Verify if the model “accepts” the draft tokens

- In the best case, add N+1 tokens in one forward pass

- In the worst case, add one token as in standard autoregressive generation

Acceptance rate is defined as the number of accepted draft tokens divided by the total number of tokens in the generated sequence.

Speculative decoding doesn’t change the model’s output—it just produces identical results faster by reducing the number of required forward passes.

Chemically Specific Drafting Strategy

The authors leverage a key insight about chemical reactions: large molecular fragments typically remain unchanged, meaning reactant and product SMILES share common substrings.

Their drafting strategy: 1. Extract subsequences of a chosen length from the query SMILES 2. Use these subsequences as drafts with a high acceptance rate

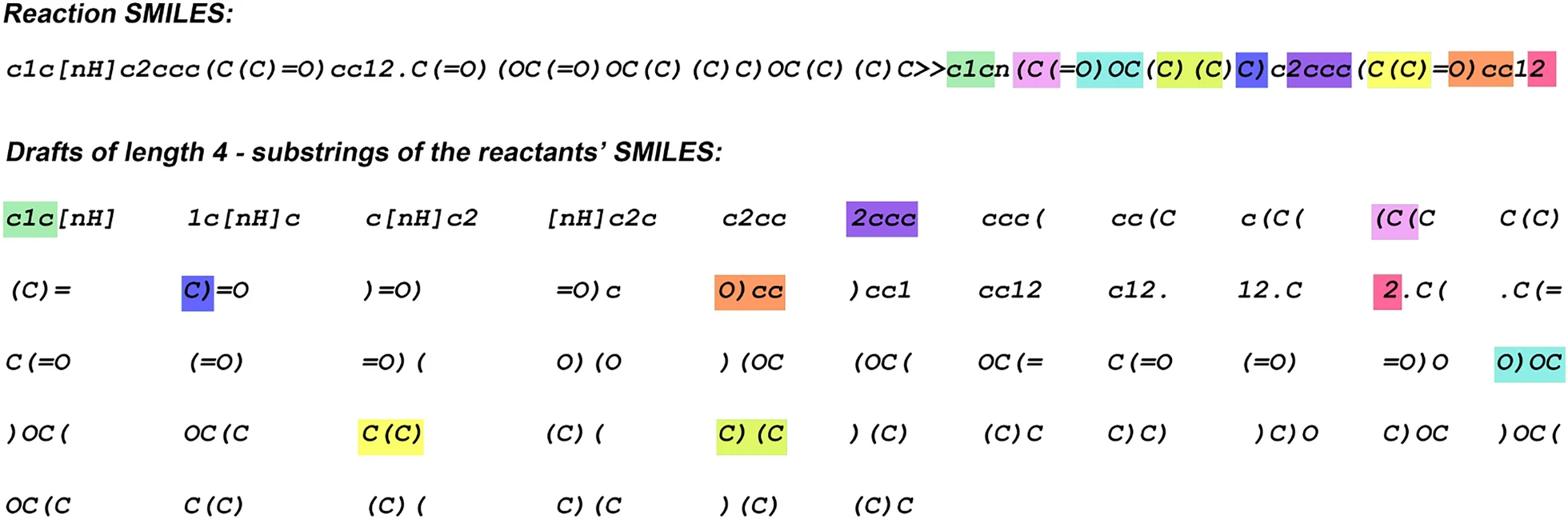

- Speculative decoding accelerates product prediction using the Molecular Transformer or a similar autoregressive SMILES generator. - Before output generation, a list of subsequences (e.g., of length four) is prepared from the tokenized query SMILES of reactants. - At each generation step, the model can copy up to four tokens from one of the draft sequences to the output. - This allows the model to generate one to five tokens in a single forward pass. - Colors are used to highlight the best draft sequence at each decoding step.

- Speculative decoding accelerates product prediction using the Molecular Transformer or a similar autoregressive SMILES generator. - Before output generation, a list of subsequences (e.g., of length four) is prepared from the tokenized query SMILES of reactants. - At each generation step, the model can copy up to four tokens from one of the draft sequences to the output. - This allows the model to generate one to five tokens in a single forward pass. - Colors are used to highlight the best draft sequence at each decoding step.

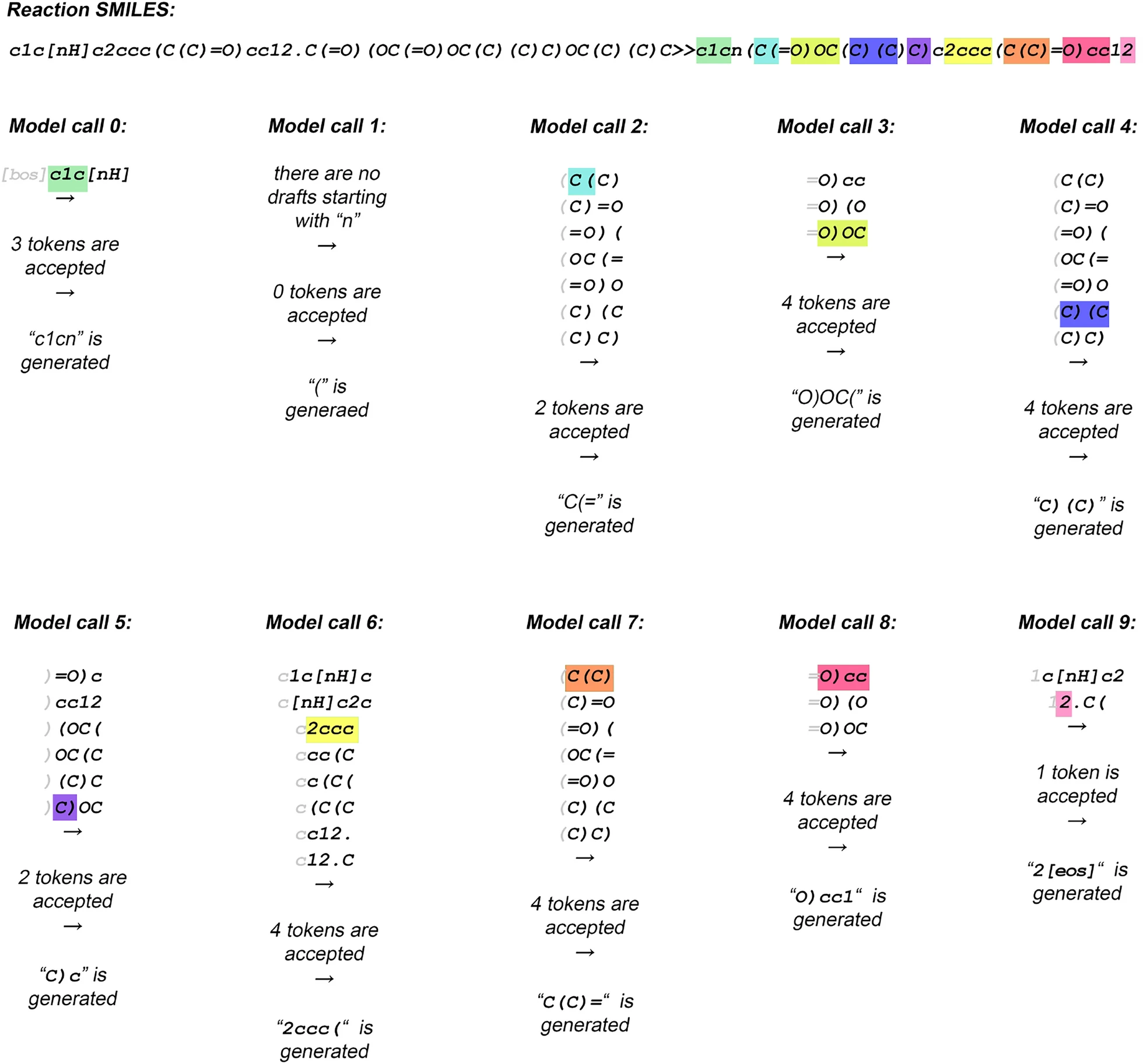

The authors also propose a “smarter” drafting strategy that only considers substrings starting with the token currently concluding the generated output:

- An improvement over the naive drafting strategy (as shown in Fig. 2) is to consider only drafts that begin with the token currently at the end of the generated output. - For the initial model call, only substrings of the source sequence that start with the

- An improvement over the naive drafting strategy (as shown in Fig. 2) is to consider only drafts that begin with the token currently at the end of the generated output. - For the initial model call, only substrings of the source sequence that start with the [BOS] token are considered—typically, there is only one such subsequence. - The first token of the selected subsequence (highlighted in gray) is stripped, and the remaining tokens are used as the draft. - After two model calls, only subsequences starting with the token “(” are considered, and this starting token is stripped to form the final drafts. - This selective drafting continues at each step, aligning the draft with the last generated token to ensure coherence.

Speculative Beam Search

For practical applications in CASP, generating multiple candidate sequences per query is essential. The authors introduce Speculative Beam Search (SBS), which combines beam search with speculative decoding:

Algorithm 1: Speculative Beam Search

Input: SB×Ls - query token sequence (tensor of integers)

K - number of best sequences to maintain

N - number of drafts

D - number of tokens in a draft

B - batch size

Ls - source sequence length

Lg - length of output generated so far

Lgm - maximum requested length of generated sequence

V - model's vocabulary size

E - dimensionality of token embeddings

1: MB×Ls×E ← ENCODER(S)

2: GB×K×1 ← [BOS] # Initialize with beginning-of-sequence token

3: DB×N×D ← MAKEDRAFTS(S, N, D)

4: repeat

5: GDB×K×Lg+D ← CONCAT(G, D)

6: LB×K×(Lg+D)×V ← DECODER(GD, M)

7: D*B×K×D ← BESTDRAFT(L)

8: TB×M×Lg+D+1 ← SEQTREE(D*, L, G)

9: GB×K×Lg+D+1 ← EXTRACTTOP(T, K)

10: until Lg = Lgm; return GThe algorithm features several key functions: - MAKEDRAFTS: Produces subsequences from the query - CONCAT: Concatenates sequences with drafts - DECODER: Forward pass of the decoder - BESTDRAFT: Selects the best draft for each sequence - SEQTREE: Creates candidate sequence trees - EXTRACTTOP: Keeps top K sequences

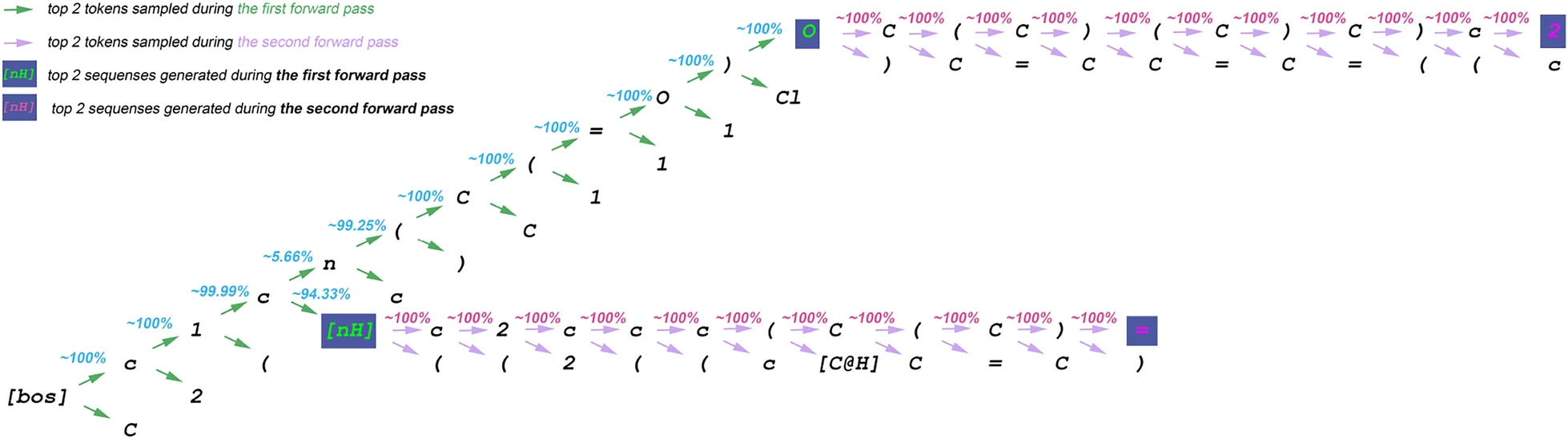

This example illustrates the first two iterations of candidate sequence tree sampling in speculative beam search (SBS), using a batch with one query sequence and maintaining two generated sequences.

At each iteration, the two best candidate sequences are selected.

The draft length \(D\) is 10 in this example.

First iteration:

- The best draft is

c1cn(C(=O), which is concatenated with the[BOS]token. - The first forward pass generates 12 candidate sequences.

- The top two sequences from this iteration are

c1c[nH]andc1cn(C(=O)O, which are retained as the current “beams”.

- The best draft is

Second iteration:

The best draft for the first beam (

c1c[nH]) isc2ccc(C(C).The best draft for the second beam (

c1cn(C(=O)O) isC(C)(C)C)c.The second forward pass produces 24 candidate sequences.

All candidates are sorted by probability, and the top two are selected:

c1c[nH]c2ccc(C(C)=c1cn(C(=O)OC(C)(C)C)c2

After two iterations, SBS produces sequences of lengths 15 and 22, respectively.

In contrast, standard beam search would have generated only two sequences of length 2 at this point.

In standard beam search, we maintain the K most probable sequences at each step. Greedy decoding is essentially beam search with K=1. Beam search is crucial for generating diverse candidates in both reaction prediction and retrosynthesis.

Results

The authors evaluate their methods on standard benchmarks for chemical reaction prediction and retrosynthesis.

Product Prediction (USPTO MIT)

Greedy Decoding Acceleration:

| Decoding | Time (B=1), min | Time (B=4), min | Time (B=16), min | Time (B=32), min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greedy | 190.5 ± 36.0 | 81.8 ± 12.3 | 28.7 ± 2.3 | 16.8 ± 1.8 |

| Speculative Greedy | 53.9 ± 3.6 | 28.8 ± 3.2 | 18.2 ± 1.0 | 14.2 ± 0.3 |

The optimal drafting parameters vary with batch size due to the throughput-latency trade-off: - B=1: 23 drafts of length 17 - B=4: 15 drafts of length 14 - B=16: 7 drafts of length 7 - B=32: 3 drafts of length 5

Beam Search Acceleration:

| Decoding (K=5) | Time (B=1), min | Time (B=2), min | Time (B=3), min | Time (B=4), min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beam search | 297.9 ± 20.2 | 166.5 ± 32.0 | 151.8 ± 19.4 | 87.7 ± 13.8 |

| SBS | 140.4 ± 7.2 | 109.1 ± 3.6 | 93.3 ± 1.3 | 82.1 ± 0.6 |

Most importantly, the accuracy remains virtually identical between standard and speculative methods:

| Metric | Beam search | SBS |

|---|---|---|

| Top-1, % | 88.425 | 88.425 |

| Top-3, % | 93.690 | 93.690 |

| Top-5, % | 94.733 | 94.720 |

Single-Step Retrosynthesis (USPTO 50K)

Beam Search at Different Beam Widths:

| Decoding (B=1) | Time (K=5), min | Time (K=10), min | Time (K=15), min | Time (K=20), min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beam search | 66.7 ± 11.1 | 70.0 ± 13.2 | 71.3 ± 14.9 | 72.2 ± 15.9 |

| SBS | 28.9 ± 2.9 | 39.2 ± 3.4 | 45.5 ± 1.2 | 47.2 ± 1.2 |

SBS with Smart Drafts:

| Decoding (K=10) | Time (B=1), min | Time (B=2), min | Time (B=4), min | Time (B=8), min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beam search | 70.0 ± 13.2 | 42.1 ± 6.7 | 26.9 ± 3.5 | 18.7 ± 1.2 |

| SBS | 39.2 ± 3.4 | 30.1 ± 0.8 | 28.1 ± 0.3 | 20.1 ± 0.2 |

| SBS (smart drafts) | 22.7 ± 1.3 | 16.6 ± 0.4 | 14.8 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 0.1 |

Again, accuracy is preserved:

| Metric | Beam search | SBS (smart drafts) |

|---|---|---|

| Top-1, % | 52.077 | 52.077 |

| Top-5, % | 82.069 | 82.069 |

| Top-10, % | 88.918 | 88.978 |

Takeaways

- Speculative decoding can accelerate transformer-based chemical reaction models by 2-3× without compromising accuracy

- The natural similarities between reactant and product SMILES enable effective chemical-specific drafting strategies

- The acceleration diminishes with larger batch sizes due to the throughput-latency trade-off

- The proposed Speculative Beam Search algorithm successfully addresses the need for generating multiple candidates

- This approach requires no model retraining or architectural changes, making it immediately applicable to existing systems

- These acceleration techniques could make transformer-based models more viable for industrial CASP applications

Future work could focus on developing more efficient drafting strategies with fewer, more accurate drafts to further improve performance at larger batch sizes and beam widths.

References

- Andronov, M., Andronova, N., Wand, M., Schmidhuber, J., & Clevert, D. A. (2025). Accelerating the inference of string generation-based chemical reaction models for industrial applications. Journal of Cheminformatics, 17(31). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-025-00974-w

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

- Segler, M. H., Preuss, M., & Waller, M. P. (2018). Planning chemical syntheses with deep neural networks and symbolic AI. Nature, 555(7698), 604-610.

- Schwaller, P., Laino, T., Gaudin, T., Bolgar, P., Hunter, C. A., Bekas, C., & Lee, A. A. (2019). Molecular transformer: A model for uncertainty-calibrated chemical reaction prediction. ACS Central Science, 5(9), 1572-1583.

- Leviathan, Y., Kalman, M., & Matias, Y. (2023). Fast inference from transformers via speculative decoding. International Conference on Machine Learning, 19274-19286.

- Irwin, R., Dimitriadis, S., He, J., & Bjerrum, E. J. (2022). Chemformer: a pre-trained transformer for computational chemistry. Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 3(1), 015022.